What are features of dermatomyositis in adults & children?

Dermatomyositis is a type of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy, which is a group of immune-mediated disorders that cause inflammation and weakness in the muscles. Dermatomyositis is characterized by muscle weakness and/or chronic inflammation of the skin, leading to a distinctive skin rash, which often appears as a purplish or violet discoloration on the eyelids, face, neck, and upper chest. The rash may also appear on the knuckles, elbows, and knees.1,2

Dermatomyositis is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.3 In addition to the skin rash and muscle weakness, people with dermatomyositis may also experience shortness of breath, cardiac symptoms, difficulty swallowing and an increased risk of malignancy.2

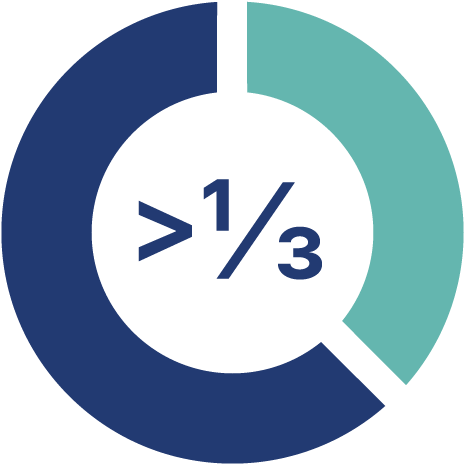

Dermatomyositis accounts for over one third of cases of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy.4

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies

The precise pathogenesis of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies is not well understood and involves many immunological pathways.2,5

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies are classified according to their patterns of presentation, age of onset, immunohistopathologic features, and treatment response.2

Identification of myositis-specific autoantibodies has improved the characterisation of myositis subtypes and associated clinical phenotypes – which vary in the severity of muscle involvement, extramuscular manifestations, and risk of malignancy.1

Overlap myositis, which includes anti-synthetase syndrome, is the most common idiopathic inflammatory myopathy and accounts for up to half of cases4. It is defined as

- Myositis associated with another defined collagen vascular disease2, e.g. systemic lupus erythematous, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, or systemic sclerosis1

- Presence of “overlap autoantibodies” including myositis-specific antibodies (MSA) or myositis-associated autoantibodies (MAA)2

Anti-synthetase syndrome may have similar clinical/pathological features to a number of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (dermatomyositis, polymyositis or necrotising autoimmune myopathy), but clinically evident myositis may be absent.2

Dermatomyositis accounts for over one third of cases of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy.4

Overview Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies:

- Dermatomyositis (DM)

Dermatomyositis typically occurs as proximal muscle weakness and/or a characteristic skin rash.2 - Polymyositis (PM)

Polymyositis affects many different muscles, particularly around the neck, shoulders, back, hips and thighs.2 - Necrotising autoimmune myopathy (NAM)

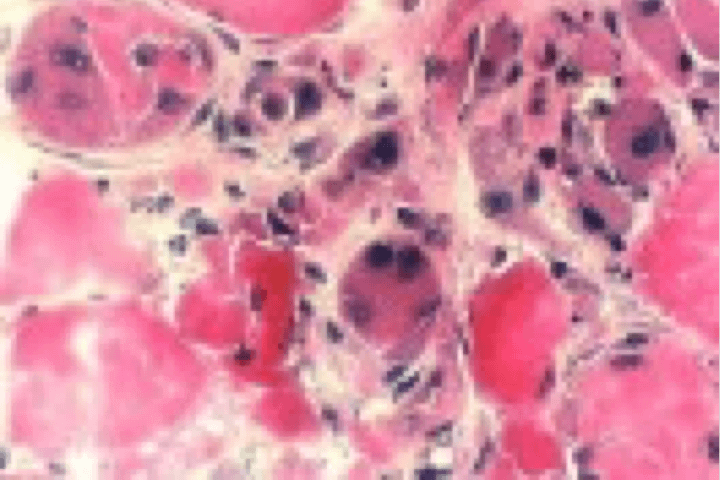

This subgroup is characterized by scattered necrotic muscle fibres and acute or subacute proximal weakness in arms and legs and very high creatine kinase levels.2,4 - Sporadic-inclusion body myositis (sIBM)

Inclusion body myositis (IBM) is the most common acquired myopathy after the age of 50.8,16 Inclusion body myositis presents with progressive insidious weakness, often asymmetric, predominantly affecting the quadriceps and/ or finger flexors8. Dysphagia is seen in more than 50% of patients with inclusion body myositis.17

Features of dermatomyositis in comparison with other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies1,2

Some key features of dermatomyositis in comparison with other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies include:

Rash: One of the most distinctive features of the autoimmune disease called dermatomyositis is a characteristic rash that appears on the skin, often on the face, neck, and upper chest. The rash may be purplish or reddish and may be accompanied by scaling.

Skin changes: In addition to the rash, people with dermatomyositis may also experience other skin changes, such as thinning of the skin, scarring, and development of calcifications.

Muscle weakness: Like other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, dermatomyositis may cause muscle weakness, even though not all patients experience muscle symptoms. Muscle involvement mainly affects multiple proximal muscle groups, including those in the neck, shoulder, hip, and upper and lower extremities.

Find more details on the table below. Compare with other inflammatory myopathies by clicking the button on the right side:

| Dermatomyositis (DM) | Polymyositis (PM) | Necrotising autoimmune myopathy (NAM) | Sporadic-inclusion body myositis (sIBM) | |

| Onset and disease course | ||||

| Age at onset |

|

|

| |

| Symptoms, specific features |

| |||

| Muscle pathology | ||||

| Treatment response |

|

|

|

|

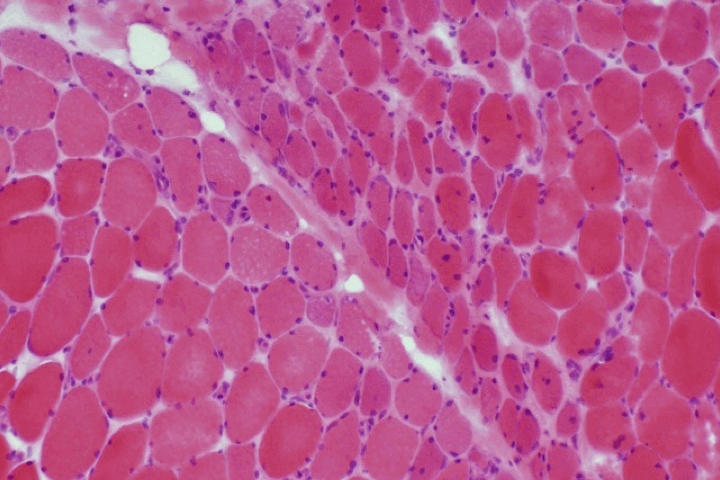

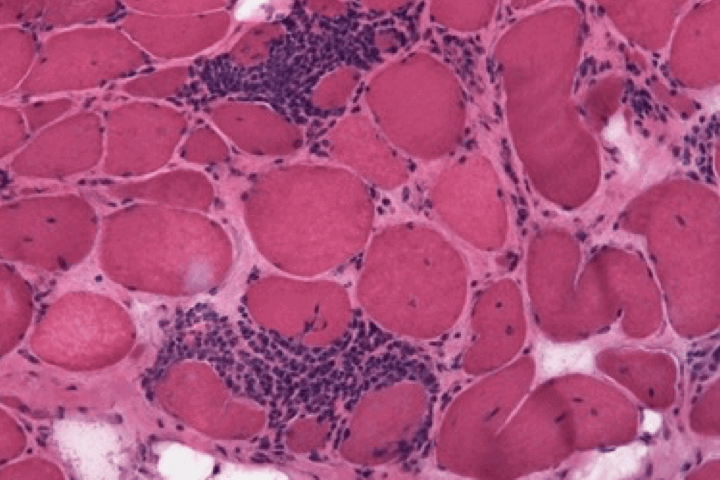

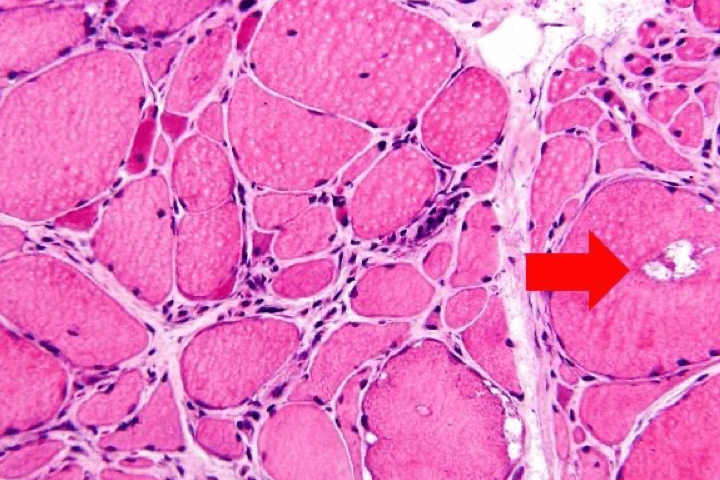

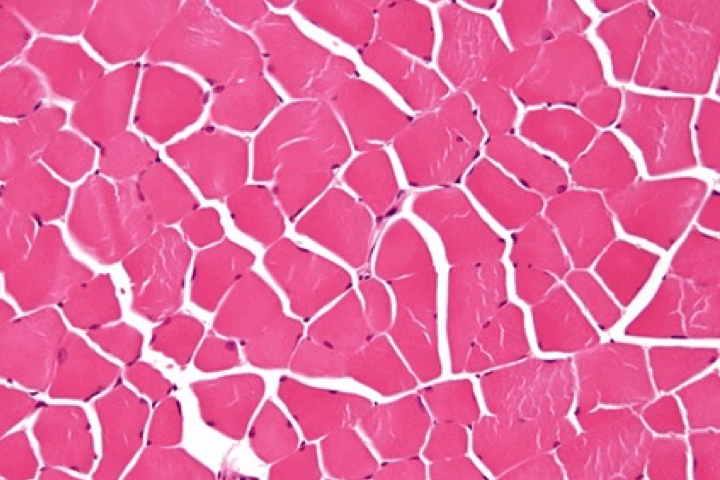

| Histological section (images courtesy of Prof. Patrick Cherin) |  |  |  |  |

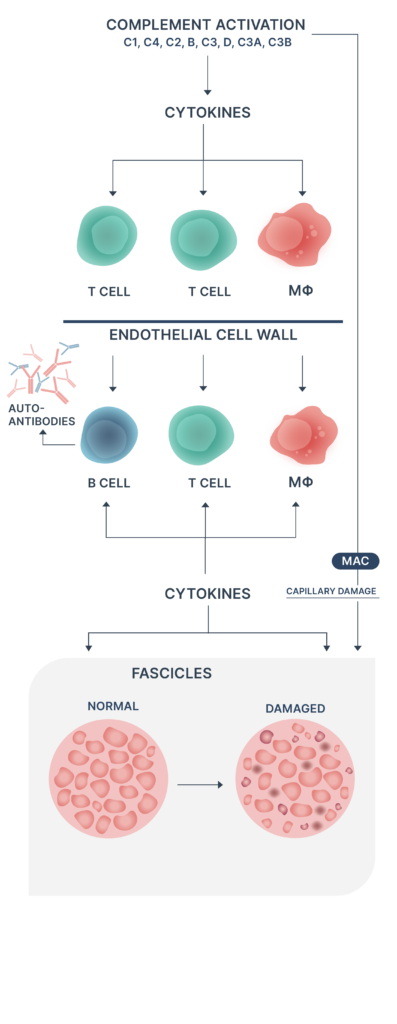

Dermatomyositis is believed to be caused by complement-mediated microangiopathy and toxicity of type I interferon.12,15

Epidemiology

Epidemiological data for idiopathic inflammatory myopathies are scarce, partly due to the rarity of this group of diseases.1,6

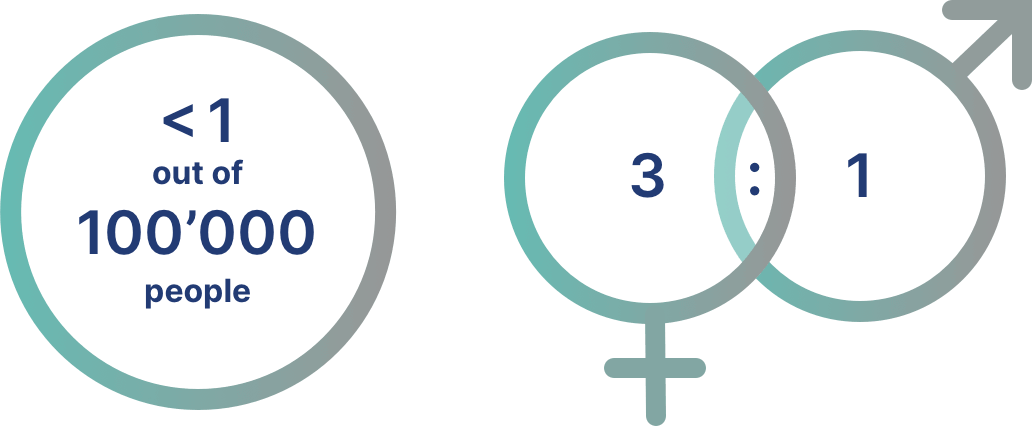

The incidence of dermatomyositis has been estimated to be < 1 case per 100,000 persons.7

One study in the US showed that the incidence and prevalence of dermatomyositis is 1.4 and 5.8 cases per 100,000 persons, respectively.1

Dermatomyositis occurs more commonly in females than in males7-9, with a ratio of approximately 3:19,10

Immunopathogenesis

Each idiopathic inflammatory myopathy phenotype likely results from different pathogenic mechanisms due to interactions between genetic risk factors and environmental risk factors.11

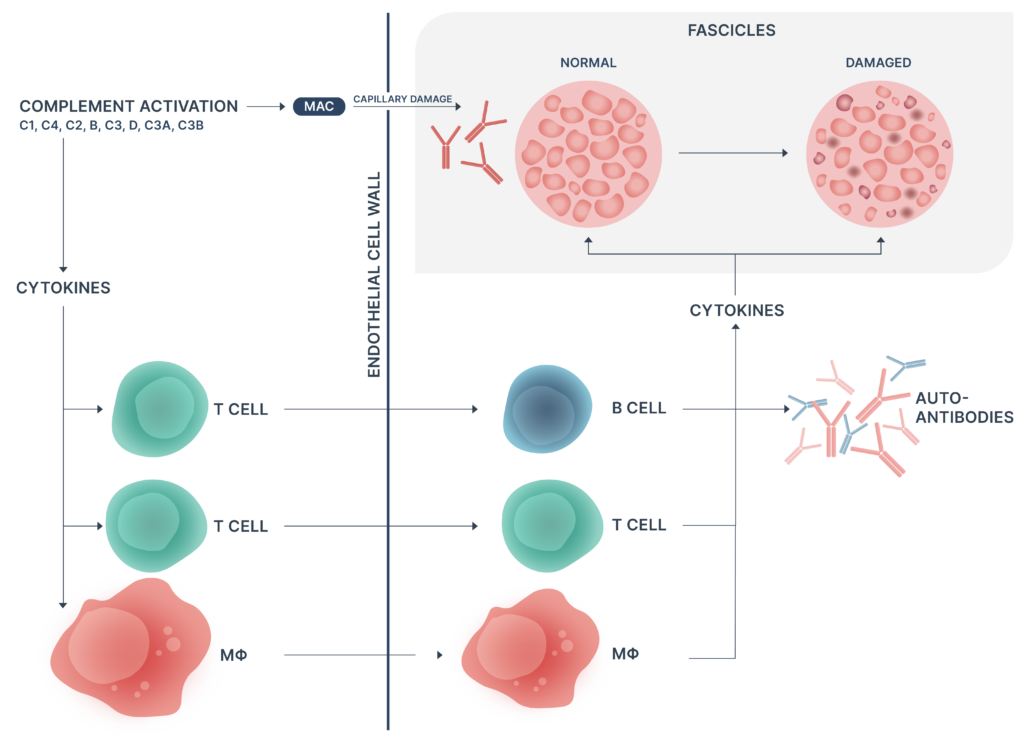

Dermatomyositis is a complement-mediated microangiopathy affecting skin and muscle. Activation and deposition of complement results in lysis of endomysial capillaries and muscle ischaemia.6,8,12

- Autoantibodies against endothelial cells may trigger complement component 3 (C3) activation

- Activation of B cells, CD4+ T cells, macrophages & MAC complex deposition

- Perivascular inflammation, capillary loss, remaining capillary dilatation, and muscle ischaemia

- Phagocytosis, necrosis and perifascicular atrophy of muscle fibres

High levels of type I interferon (IFN-I) are found in muscles of dermatomyositis patients with overexpression of IFN-I induced genes in muscles, skin and blood, the latter demonstrated in some cases to be correlated with disease activity.11,13

Interstitial lung disease is the leading cause of death in patients with dermatomyositis.1

Prognosis

Dermatomyositis is associated with increased morbidity and mortality due to muscle weakness and visceral involvement.3

- Patients with dermatomyositis have a nearly 8-fold increase in their risk of death during a 10-year follow-up compared with the matched general population.14

- In a nationwide retrospective study in Finland, 58% of patients died during a 20-year follow-up.10

Malignancies and diseases of the circulatory and respiratory system are common causes of death in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies14, with interstitial lung disease the leading cause of death in dermatomyositis.1

Risk factors for death include older age, cancer, respiratory and cardiac involvement, dysphagia and certain myositis-specific autoantibodies.3

Cancer screening is advisable for patients with autoantibody subtypes that are associated with increased risk of malignancy.1

References

- Goyal NA. Immune-Mediated Myopathies. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology, 25(6), 1564–1585. https://doi.org/10.1212/con.0000000000000789

- Malik, A., Hayat, G., Kalia, J. S., & Guzman, M. A. (2016). Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies: Clinical Approach and Management. Frontiers in Neurology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2016.00064

- Marie, I. (2012). Morbidity and Mortality in Adult Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis. Current Rheumatology Reports, 14(3), 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-012-0249-3

- Schmidt, J. (2018). Current Classification and Management of Inflammatory Myopathies. Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases, 5(2), 109–129. https://doi.org/10.3233/jnd-180308

- Oddis, C., & Aggarwal, R. (2018). Treatment in myositis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2018.42

- Briani, C., Doria, A., Sarzi-Puttini, P., & Dalakas, M. C. (2006). Update on idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Autoimmunity, 39(3), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/08916930600622132

- Okogbaa, J., & Batiste, L. (2019). Dermatomyositis: An Acute Flare and Current Treatments. Clinical Medicine Insights. Case Reports, 12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179547619855370

- Dalakas, M. C., & Hohlfeld, R. (2003). Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. The Lancet, 362(9388), 971–982. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14368-1

- Dankó, K., Ponyi, A., Constantin, T., Borgulya, G., & Szegedi, G. (2004). Long-term survival of patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies according to clinical features: a longitudinal study of 162 cases. Medicine, 83(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.md.0000109755.65914.5e

- Airio, A., Kautiainen, H., & Hakala, M. (2006). Prognosis and mortality of polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients. Clinical Rheumatology, 25(2), 234–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-005-1164-z

- Miller, F. W., Lamb, J. A., Schmidt, J., & Nagaraju, K. (2018). Risk Factors and Disease Mechanisms in Myositis. Nature Reviews. Rheumatology, 14(5), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2018.48

- Dalakas, M.C. (2015). Inflammatory Muscle Diseases. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(18), pp.1734–1747. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra1402225.

- Pinal-Fernandez, I., Casal-Dominguez, M., Derfoul, A., Pak, K., Plotz, P., Miller, F. W., Milisenda, J. C., Grau-Junyent, J. M., Selva-O’Callaghan, A., Paik, J., Albayda, J., Christopher-Stine, L., Lloyd, T. E., Corse, A. M., & Mammen, A. L. (2019). Identification of distinctive interferon gene signatures in different types of myositis. Neurology, 93(12), e1193–e1204. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000008128

- Dobloug, G. C., Svensson, J., Lundberg, I. E., & Holmqvist, M. (2018). Mortality in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: results from a Swedish nationwide population-based cohort study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 77(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211402

- R. Aggarwal, C. CharlesSchoeman, J. Schessl, Z. BataCsörgő, M.M. Dimachkie, Z. Griger, S. Moiseev, C. Oddis, E. Schiopu, J. Vencovský, I. Beckmann, E. Clodi, O. Bugrova, K. Dankó, F. Ernste, N.A. Goyal, M. Heuer, M. Hudson, Y.M. Hussain, C. Karam, N. Magnolo, R. Nelson, N. Pozur, L. Prystupa, M. Sárdy, G. Valenzuela, A.J. van der Kooi, T. Vu, M. Worm, and T. Levine, for the ProDERM Trial Group (2022). Trial of Intravenous Immune Globulin in Dermatomyositis. New England Journal of Medicine, 387, 1264-1278. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2117912

- Naddaf, E., Barohn, R.J. and Dimachkie, M.M. (2018). Inclusion Body Myositis: Update on Pathogenesis and Treatment. Neurotherapeutics, 15(4), pp.995–1005. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-018-0658-8

- Labeit, B., Pawlitzki, M., Ruck, T., Muhle, P., Claus, I., Suntrup-Krueger, S., Warnecke, T., Meuth, S.G., Wiendl, H. and Dziewas, R. (2020). The Impact of Dysphagia in Myositis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(7), p.2150. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9072150

Science Hub

Sign up and connect to Science Hub to learn more about our recent ProDERM study and have access to symposia presentations, publications, posters and lectures.